Friends Called Him Jimmy

On James Baldwin, the wretched of the earth and the burden of witness.

In 1971, two British filmmakers flew to Paris to make a documentary on James’ life as a writer called Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris. When filming began in earnest Baldwin’s attitude changed. He declined all questions and even denied them permission to film him. He simply refused to cooperate. In one scene, Baldwin and the filmmakers stood before the Place de la Bastille, a memorial for the French Revolution. After increasingly heated exchanges as Terrence, the director, tried to determine the source of Baldwin's uncooperativeness, Baldwin finally confessed. “I cannot speak to you,” he said. “I need to speak to someone who can understand.”

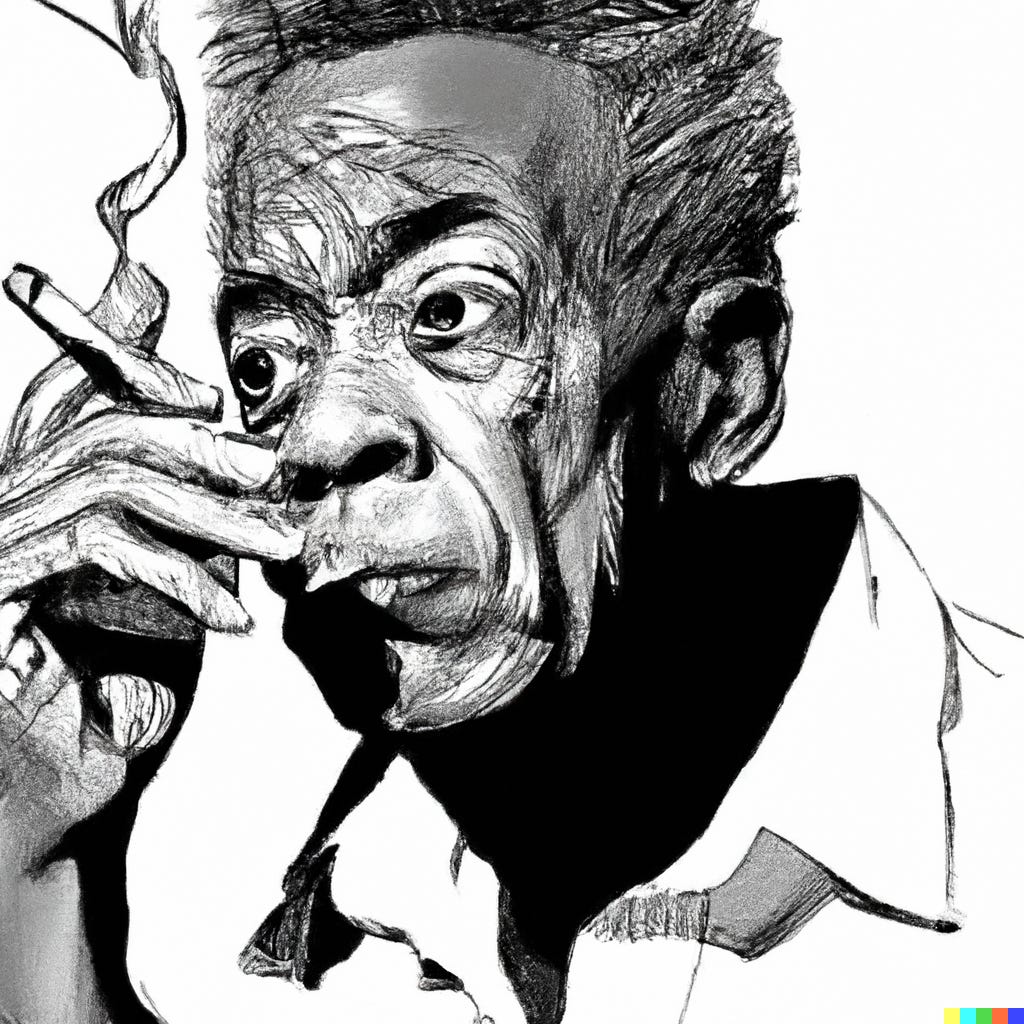

Of all the ways to describe a person, starting with their eyes might be the most trite. Yet I find it hard to think of any other way to describe James Baldwin without first mentioning his large eyes (those pupils wide and dark as udara seeds sucked clean!) that shined with a moist glisten, as though he was eternally on the verge of tears, and in other moments seemed to disappear deep into the ridges of his flesh whenever a gap-toothed smile crumpled his face. Part of me secretly wished for him to break down in tears in any of the recorded interviews; the tension was unbearable.

The unbounded nature of words on paper invariably compels a writer to stray out of the familiar (or unfamiliar) space of their body and into the wider world, into other people and other problems. But what is this astral effort in service of? Does the writer use the exterior world to understand their own lives better, or do they turn to their internal experiences to unravel the mystique of society? In any case, Baldwin The Witness was deeply aware of his place in the world. He spoke frequently of his responsibility to the wretched of the earth for which he was spokesman and confessor. Baldwin knew he was in the unenviable situation of being one of a handful of black people who had a voice in the middle of the 20th century.

He served as a witness to death in its various forms. The 2017 movie, I Am Not Your Negro, detailed the particular devastation Baldwin experienced after the deaths of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. Byron De La Beckwith shot and killed Medgar, an activist and close friend to Baldwin, right in his driveway. All-white juries found Byron not guilty of the murder on two separate occasions. It was not until 1994 that the case was reopened at the insistence of Medgar’s widow, and the killer was finally found guilty by a majority black jury. Byron was sentenced to life in prison at the age of 71. Baldwin, despite his role as witness, did not live to see this belated justice for his murdered friend. Byron died in prison at age 80; Medgar was 37 when he was killed. Malcolm X was killed at the age of 39, as was Martin Luther King; Baldwin was present for all three funerals.

He also witnessed the intangible death of dreams. By the time Baldwin published, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, in 1985, the USA lay tense in its post-civil rights era bed, the Apple Macintosh computer had spent a year on the market, and people had accepted racial integration as a self-evident truth. But Baldwin was deeply suspicious – even critical – of integration and viewed it as a deviation from the original goal of desegregation. Desegregation, in its original form, would have allowed the black people of America to preserve the parallel institutions they had built from scratch and refined over the centuries-long othering endured at the hands of white power the moment the first slave alighted onto the wet plank of a Virginia port. Black Americans had established alternative financial institutions, cooperative societies, farms, schools, churches and neighbourhoods. Desegregation would simply outlaw the barriers that artificially separated the populations.

On the other hand, integration was coloured by a fatal belief in the malleability of human love and that it was possible – by legislative means – to stretch the heart of the white majority and create space for their darker siblings. But laws and amendments can only do so much. It is one thing to outlaw discrimination, and it is another thing entirely to arbitrate yourself into acceptance. Integration, it was argued, was not worth the effort. Firstly, whiteness was a thing that was created to be as different from blackness as possible. Trying to compel white people to accept their darker siblings was futile because that meant that the white identity would have to be dismantled. Secondly, integration caused black Americans to abandon their parallel institutions so much so that the only one that has survived until now is the Black Church1. I suspect that the Black Church’s endurance comes from the fact that the black and white populations in the USA use Christianity to achieve very different goals (The same occurs in Nigeria, but I will revisit this in a future essay). Figures like Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey were vocal in their opposition to integration. Baldwin himself asked pointedly, “Is it worth integrating into a sinking ship?”

A striking aspect of his recorded interviews is how often he alludes to his failure. Baldwin’s artistic output was for humanity; I am certain he would cringe at being labelled a black writer. Yet, he was well aware that precisely the same people who would have benefitted the most from hearing his message were the same ones who would refuse any such understanding. They go by many names: White Capital, the World Order, the Ruling Class, or any such designation that elevates some groups at the expense of others who are relegated to the bottom.

I have not written anything substantial to earn the ignominy of being called a writer, but in the short period in which I wrote fiction, I was crippled by a fear of not having anything to say and not finding the right ways to say it. But this dilemma is simpler than that which faces one whose writing scales those initial hurdles only to be confronted with a mind impervious to persuasion, or, even worse, moral responsibility. So, why did he persist? Perhaps the answer is in his relationship with those he described as the wretched of the earth. He was aware of and accepted the responsibility to “witness” for these people. And I believe Baldwin was much too proud a man to shirk that responsibility despite the measure of failure that was guaranteed to come with it.

I call him proud but I never met the man. I often wonder who exactly was the man Baldwin, familiar yet distant as he was. We cannot call him a revolutionary writer. In his words, “I am just a writer in a revolutionary situation.” Critics accused him of selling out and even becoming a tool for white oppression, especially in the later years of his career. We cannot call him a fearless civil rights legend but he did give a voice to its spirit. He was a preacher who ended up vehemently denouncing religion. His friends called him Jimmy. He once had a romantic relationship with a 17-year-old Swiss boy. He was prone to colourful and expressive speech littered with obliquities that teased an audience towards a truth he seemed to have already reached. He was a very Homosexual and very Black man and endured a two-pronged social stigma as a result. His stepfather once told him he was the ugliest child he had ever seen.

Standing in front of the Place de la Bastille, his eyes still wet despite the biting cold, Baldwin seems small and exposed. Behind him rises a monument to a specific type of liberation, formidable in size and in the number of lives sacrificed to secure it. In front of him, several British men, frustrated at his uncooperative spirit, ask him why he ignores their questions as he wonders how the imagery of the situation is lost on them. Later, in another scene, Baldwin is finally cooperative and speaks to the filmmakers indoors. He wears a simple tweed jacket and appears to be freshly shaven. Terence, the director and interviewer, asks Baldwin what he thinks of the people who say Baldwin is there in Paris because he has escaped.

“What have I escaped from?” Baldwin asks, a smile crumpling his features. “Where, anyway, in the world can a black man who is fleeing escape to?”

March 2, 2024

The next day after this was initially published, my good friends, Toyin and Nneoma, informed me that this assertion was not accurate. HBCUs exist today, for example. I accept that I overstepped here and commented on a history of which I do not have the most nuanced understanding. I am thus adding this belated footnote.